Base and Superstructure Explained: How Marxism Helps Us Understand Society

A clear guide to Marxist theory, showing how economics, culture, and politics interact and why it matters today.

If Marxism really claimed that “the economy controls everything,” it would be both intellectually shallow and politically useless. Yet this is how base and superstructure are almost always presented—by critics and, unfortunately, by some self-described Marxists as well. The result is a theory stripped of its dialectic and a politics that oscillates between economism and cultural wish-casting.

At the same time, much of the contemporary left has moved in the opposite direction, treating politics as a struggle fought almost entirely at the level of discourse, representation, and moral persuasion. We are told that changing language, winning narratives, or achieving cultural recognition is itself transformative, even as the underlying organization of production, property, and power remains intact. Rhetoric displaces results.

Marx’s concept of base and superstructure was developed precisely to explain why neither of these approaches works. It is not a claim that ideas are irrelevant, nor that culture is a passive reflection of “the economy.” It is an attempt to theorize the structured relationship between how society produces its material life and how that society understands, justifies, and reproduces itself.

To understand what this means, and why it matters, we need to be precise about what Marx meant by base and superstructure, and equally precise about what he did not mean.

The Framework

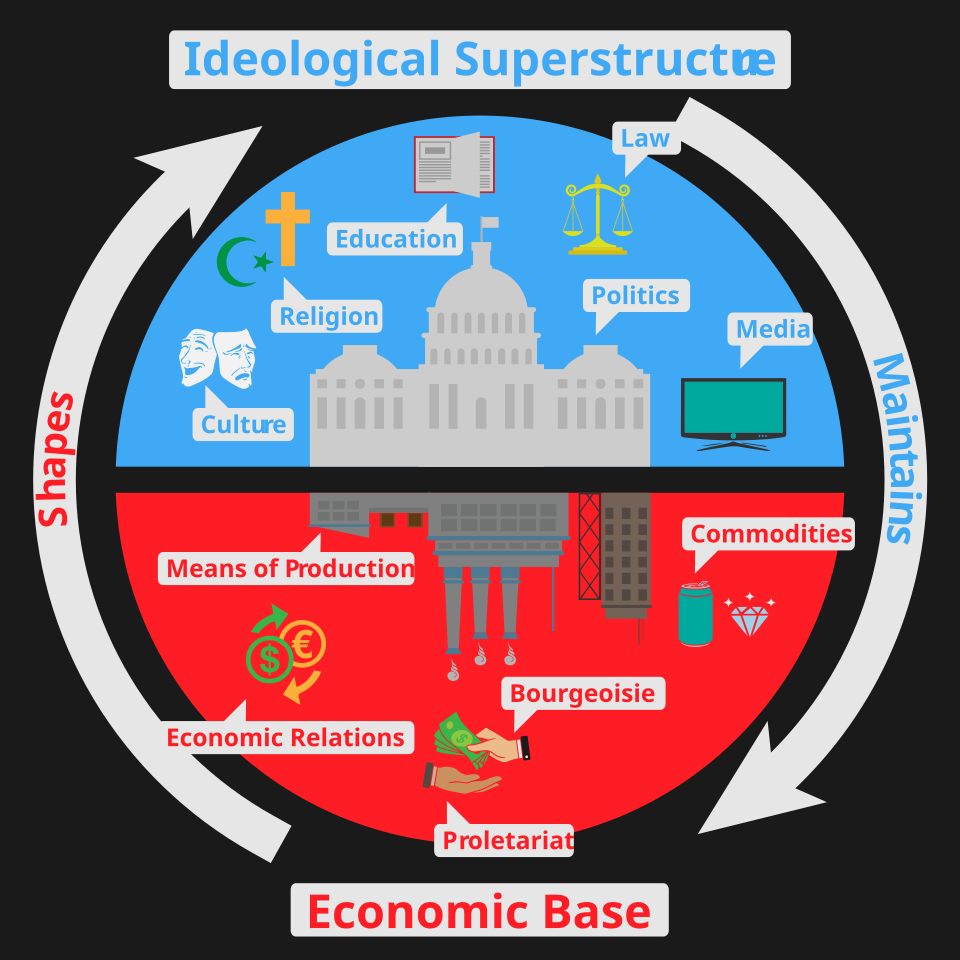

In Marxist theory, base and superstructure describe a structured and reciprocal relationship between a society’s mode of production (the base) and the political, legal, and ideological forms (the superstructure) that arise from it. The economic base does not mechanically dictate ideas or institutions, but it does set the limits within which they develop, stabilize, and are contested. Superstructural forms—law, the state, culture, and ideology—possess real power and relative autonomy, yet their primary historical function is to reproduce or manage the underlying relations of production.

To misunderstand this relationship is to mistake surface change for structural transformation, and to repeatedly confuse political motion with political progress.

Marx’s most explicit formulation of the relationship between base and superstructure appears in the 1859 Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. There, he argues that the “mode of production of material life conditions the social, political, and intellectual life process in general.” This formulation is often reduced to a crude claim that economic activity directly produces ideas.

In fact, Marx is describing a structural relationship. Human beings enter into definite relations of production in order to survive, and these relations form the real foundation upon which legal and political institutions arise. Consciousness, in this account, is not fabricated in the abstract but develops within historically specific material conditions.

Friedrich Engels later clarified this relationship in an 1890 letter to Joseph Bloch, explicitly warning against the idea that Marxism reduces history to a single economic cause. While the economic structure of society is decisive “in the last instance,” Engels emphasized that political struggles, legal systems, traditions, and ideological forms exert real influence and can shape the course of historical development. To ignore this reciprocal action, Engels argued, is to turn historical materialism into a lifeless formula rather than a method of analysis.

Lenin extends this framework into the realm of political practice. In What Is to Be Done?, he rejects the notion that socialist consciousness spontaneously emerges from economic struggle alone, insisting instead on the necessity of political organization and ideological intervention. In State and Revolution, Lenin further clarifies the class character of the state, treating it as a superstructural institution that both arises from irreconcilable class antagonisms and functions to manage them. For Lenin, the superstructure is not epiphenomenal; it is a decisive battlefield, though one whose contours are ultimately shaped by the underlying relations of production.

Antonio Gramsci deepens the concept further by theorizing how capitalist societies maintain stability without relying exclusively on coercion. Through the concept of hegemony, Gramsci shows how ruling classes secure consent by organizing cultural, educational, and ideological institutions in ways that align popular “common sense” with existing material relations. Civil society, in this framework, becomes a key site of superstructural struggle—not separate from the economic base, but intimately involved in its reproduction. Gramsci’s intervention helps explain why ideological domination often feels natural and why challenges to capitalism routinely encounter resistance even from those it exploits.

Liberal Democracy as Superstructure

Nowhere is the relationship between base and superstructure clearer than in liberal democracy itself. This is not incidental. Liberal democracy did not emerge as a neutral or timeless expression of popular will; it developed alongside capitalism as a political form capable of managing class society while presenting itself as universal, egalitarian, and non-coercive.

At the level of lived experience, liberal democracy feels intensely political. Elections are frequent, discourse is saturated, moral stakes are high, and participation is encouraged. Citizens are told, correctly, in a narrow sense, that they possess equal political rights: one person, one vote; equal standing before the law; freedom of speech and association. Yet this formal equality coexists with, and often obscures, a profound material inequality. The ability to shape the conditions of social life remains concentrated in the hands of those who own and control capital.

This is not a contradiction within liberal democracy; it is its function. The economic base of capitalist society—private ownership of the means of production, wage labor, and accumulation driven by profit—creates a situation in which political stability cannot rely on naked coercion alone. A system built on generalized exploitation requires legitimacy. Liberal democracy provides it.

The state, under capitalism, presents itself as neutral precisely because it must govern a society divided by class antagonism. Law appears abstract and universal; rights are framed as individual rather than social; politics is reduced to the aggregation of preferences rather than the contestation of power. These are superstructural forms suited to a mode of production that depends on formally free workers selling their labor in a market.

Formal Equality, Material Power

This is why political participation under liberal democracy often feels both meaningful and ineffective. Voting matters—but within tightly constrained limits. Parties compete, rhetoric shifts, representation changes, yet the underlying imperatives of capital accumulation remain largely untouched. Policy debates orbit questions of distribution and management rather than ownership and control. Even moments of apparent rupture are quickly absorbed, moderated, or reversed once they threaten the reproduction of the economic base.

Here the reciprocal relationship between base and superstructure becomes visible. Economic power shapes the boundaries of political possibility long before politics begins: what policies are “realistic,” what demands are “serious,” what futures are “responsible.” In turn, political institutions and ideological narratives reinforce those boundaries by framing outcomes as the result of democratic choice rather than structural constraint. When living standards decline, the problem is cast as poor leadership, polarization, or misinformation—not the organization of production itself.

Gramsci’s concept of hegemony is particularly useful here. Consent is not manufactured through deception alone but through the everyday operation of institutions that align common sense with existing material relations. Liberal democracy teaches people to understand freedom as choice within markets, equality as legal sameness, and politics as representation rather than transformation. These ideas feel natural because they correspond to how social life is materially organized. The superstructure does not simply sit atop the base; it helps reproduce it by shaping how people interpret their own experience.

This also explains why so much of contemporary politics gravitates toward culture, discourse, and representation. These are not irrelevant struggles, but they are the forms of struggle most easily accommodated by liberal democratic capitalism. They promise recognition without redistribution, inclusion without expropriation, and voice without power. Political energy is expended at the level of symbols while the underlying relations of production remain intact.

None of this means that liberal democracy is a sham or that political struggle within it is meaningless. It means that its possibilities are structured. The superstructure can mediate, delay, and even partially restrain the logic of capital, but it cannot abolish it on its own.

Seen through the lens of base and superstructure, the current crisis of liberal democracy is not primarily a crisis of norms or civility. It is a crisis of a political form stretched beyond what its material foundation can sustain. As inequality deepens and insecurity spreads, the gap between formal political equality and real social power becomes harder to ignore. The legitimacy that liberal democracy once supplied to capitalism begins to erode because the material conditions that once made that belief plausible are breaking down.

This is why understanding base and superstructure matters. Without it, political frustration is misdiagnosed as apathy, extremism, or moral failure. With it, we can see liberal democracy for what it is: a historically specific superstructural arrangement that stabilizes capitalist society by translating material domination into political legitimacy—and, in moments of crisis, struggles to do so.

What This Means for Politics

If base and superstructure describe anything more than an academic distinction, they describe the terrain on which political struggle actually occurs and the reasons so much of contemporary politics fails to move it.

Much of the left today oscillates between two errors. On one side is economism: the belief that worsening material conditions will, on their own, generate political consciousness and transformative action. On the other is idealism: the belief that changing language, culture, or representation can substitute for confronting the material organization of society. Both misunderstand the relationship Marx was trying to theorize. Material conditions shape consciousness, but they do not automatically produce it. Ideology matters, but it does not float free of the social relations that sustain it.

This is why so many movements burn intensely and then dissipate. Culture-first strategies mistake visibility for power and persuasion for transformation. They win symbolic victories that feel meaningful but leave the underlying relations of production intact. When backlash arrives, as it reliably does, those victories prove fragile, because the material basis of social life has not been altered. The superstructure adjusts, absorbs, and moves on.

At the same time, narrowly materialist approaches fare no better. Economic struggle without political organization, ideological clarity, or institutional strategy tends to be fragmented and defensive. Workers can fight for wages, conditions, and survival while remaining trapped within the ideological horizon of capitalism itself. Without intervention at the level of the superstructure—parties, unions, law, culture, and the state—material struggle is repeatedly contained, redirected, or neutralized.

A base–superstructure analysis does not license passivity; it demands strategy. It insists that socialists take institutions seriously, not as neutral arenas but as sites of class power. It requires engaging ideology not as a matter of personal belief or moral correctness, but as a material force embedded in schools, media, law, and everyday common sense. And it refuses the comforting illusion that either economic crisis or cultural change will do the work for us.

Liberal democracy, as we have seen, is particularly effective at translating material domination into political legitimacy. It encourages participation while constraining possibility, offering voice without power and choice without control. Understanding this does not mean abandoning democratic struggle; it means recognizing its limits. The question is not whether to engage the superstructure, but how—and to what end.

The recurring failure of contemporary politics is not that people are apathetic or irrational. It is that political action is repeatedly severed from material transformation, while material suffering is repeatedly interpreted through ideological frameworks that leave its causes untouched. Base and superstructure name this disconnect. They explain why politics feels omnipresent yet ineffectual, why change is promised endlessly and delivered so sparingly.

Marx’s framework remains useful not because it predicts outcomes, but because it disciplines thought. It forces us to ask where power actually resides, how it is reproduced, and what kinds of struggle can realistically challenge it. Without that discipline, politics collapses into spectacle or fatalism. With it, we can begin to distinguish between movement and progress, reform and transformation, participation and power.

Understanding base and superstructure will not, by itself, change the world. But misunderstanding it has helped ensure that much of our political energy is expended in ways that leave the world fundamentally the same. That alone should be reason enough to take the concept seriously.

Absolutely brilliant. Thanks for taking the time to make this accessible.

Strong piece on why liberal democrcy absorbs dissent so effectively. The point about how formal equality coexists with material domination isnt just descriptive, it shows the actuall mechanism of legitimation. I've seen this play out in electrol cycles where transformative demands get reframed as tweaks to distribution rather than ownership. Gramsci's hegemony concept really clarifies why so much activism ends up negotiating within those boundaries.